I first met Karl Popper’s work in 1978, when I was researching and writing my doctoral dissertation, Human Replay: A Theory of the Evolution of Media (New York University, 1979), which argued that communications media evolve in a Darwinian fashion, in which we humans select which media survive, based on how well they accommodate our need to communicate across time and space in a way that as much as possible preserves our pre-technological, natural modes of communication. Thus, talkies replaced silent movies, but radio survived the advent of television, because the natural world regularly provides occasions with sound but no vision, but rarely with vision and no sound – we can easily close our eyes but not out ears, the world grows dark every night but never really silent, etc. Silent movies (sight without sound) thus has no natural analog, whereas radio (sound without sight) does. I devoted a chapter of Human Replay to Popper’s evolutionary epistemology as presented in his Objective Knowledge, 1972, his view of human ideas as evolving via a process akin to natural selection serving as a foundation for my “anthropotropic” (“anthropo”=human; “tropic”=towards) Darwinian theory of media evolution.

When my dissertation was finished, approved in my orals, and my PhD was in hand, I realized I had a lot of unfinished business with Karl Popper. I wanted to explore the full corpus of his work. Being a proponent of John Dewey’s philosophy that we best learn through doing, I soon decided the best way I could learn all I could about Popper’s work was not only to read it but put together an anthology of essays examining all facets of his work. The timing was right. Popper’s 80th birthday was just a few years away – 1982 – and I thought my anthology could be pitched to a publisher as a Festschrift in honor of that momentous occasion. An audacious move, for someone with a newly minted PhD, but I had nothing to lose and a lot to gain.

My call for papers went so well that I soon had publishers in the United States and the United Kingdom, and essays for not just one but two volumes. The publishers were interested in only one volume, however, and In Pursuit of Truth: Essays on the Philosophy of Karl Popper on the Occasion of His 80th Birthday was published in the US and the UK in October 1982, with essays by such luminaries as John C. Eccles, W. W. Bartley III, Joseph Agassi, David Miller, Ian Jarvie, and Gerard Radnitzky, as well as my interview with Ernst Gombrich, and Forewords by Isaac Asimov and Helmut Schmidt. It was my first published book, and my wife and I had the pleasure of presenting the page proofs to Sir Karl and his wife in their modest Fallowfield home in the countryside of England in July 1982. I also organized the First International Convocation of the Open Society and Its Friends in New York City in November 1982, the first of only a handful of academic conferences I’ve organized in my academic career because, well, I’d much rather be writing, and speaking at conferences, than organizing them. The overflow essays from In Pursuit of Truth were published in the Fall of 1985 as a special issue of et cetera (Journal of the International Society of General Semantics) which I guest-edited with the assistance of Fred Eidlin. It contained articles by Popperians including Peter Munz, Larry Briskman, and Jeremy Shearmur.

In 1988, my first published solely-authored book Mind at Large: Knowing in the Technological Age argued that technology is a special and significant denizen of Popper’s World Three, with some World One characteristics, since every technology is a physical embodiment of an idea (a chair is an embodiment of an idea about how to sit), and communications media not only embody an idea about how to convey information (a printed book embodies an idea about how to preserve and transmit ideas by putting them in written words printed on paper) but also contain other ideas that are described not embodied in the book (the subject of the book or what the book is actually about).

In ensuing years, I continued to employ Popper’s work as a springboard. I attended a conference or two on Popper’s philosophy, and struck up relationships with new Popperians, including Ray Scott Percival, whom I appointed in the mid-1990s as Associate Editor of the Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, of which I was Editor-in-Chief. Ray invited me to present a paper at the Annual Popper Conference at the LSE in March 1995, and that proved to be a fortuitous conference to attend. I met an editor from Routledge at that conference, and this led in the next few years to Routledge publishing two of my best-known books, The Soft Edge: A Natural History and Future of the Information Revolution (1997) and Digital McLuhan: A Guide to the Information Revolution (1999).

I’ve had many occasions to cite Popper’s work in classes, articles, books, podcasts, and conference addresses in the years since then. Interestingly, however, I’ve had occasion in the past year or two to cite Popper not with approval but as author of an idea, now widely cited, with I strongly disagree. That idea is known as Popper’s “paradox of tolerance” (from The Open Society and Its Enemies), in which Popper contends that tolerance to those who preach intolerance and the overthrow or closing of the open society is a big mistake, because such tolerance will lead to the destruction of the tolerant, open society. I of course get Popper’s logic, but am surprised he didn’t see deeper, and realize that the moment we censor or suppress intolerant speech, we at that moment are being intolerant ourselves, and therein contributing to the suppression of the open society (see Levinson, 2018). As I often say to my students, we don’t need a First Amendment and devotion to free expression to protect speech we love. Such communication needs no protection. But we do need the First Amendment to protect speech that we hate. Because someone, some group may hate speech that we love or deem highly worthy.

So, I’m concluding this little tour of my intellectual life with Popper with a criticism of a part of his work. But that’s only appropriate, given the preeminent place Popper puts on criticism in the growth of knowledge.

References

— Levinson, Paul (1979) Human Replay: A Theory of the Evolution of Media, PhD dissertation, New York University.

— Levinson, Paul, ed. (1982) In Pursuit of Truth: Essays on the Philosophy of Karl Popper on the Occasion of His 80th Birthday. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities & Harvester, Brighton, UK.

— Levinson, Paul (1988) Mind at Large: Knowing in the Technological Age. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

— Levinson, Paul (1997) The Soft Edge: A Natural History and Future of the Information Revolution. New York & London: Routledge.

— Levinson, Paul (1999) Digital McLuhan: A Guide to the Information Revolution. New York & London: Routledge.

— Levinson, Paul (2018) “Government regulation of social media would be a cure far worse than the disease,” The Conversation, 16 February.

— Levinson, Paul and Fred Eidlin, eds. ( Fall 1985) Special issue of ETC: A Review of General Semantics, Vol. 42, No. 3.

— Popper, Karl (1945/1971) The Open Society and its Enemies, Vols 1 & 2, 5th rev. ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

— Popper, Karl (1972) Objective Knowledge. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

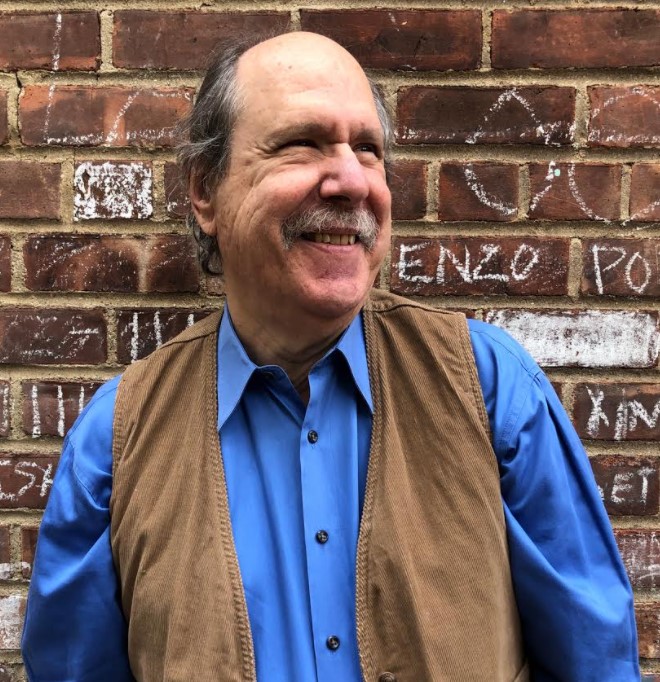

Paul Levinson

New York City, NY, USA – Contributor

Paul Levinson, PhD, is Professor of Communication & Media Studies at Fordham in NYC. His nonfiction books, including The Soft Edge, Digital McLuhan, Realspace, Cellphone, New New Media, McLuhan in an Age of Social Media, and Fake News in Real Context have been translated into 15 languages. His science fiction novels include The Silk Code (winner of the Locus Award for Best First Science Fiction Novel of 1999), Borrowed Tides, The Consciousness Plague, The Pixel Eye, The Plot To Save Socrates, Unburning Alexandria, and Chronica. His award-nominated novelette, “The Chronology Protection Case,” was made into a short film and is on Amazon Prime Video. He appears on CBS News, CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, the History Channel, and NPR. His 1972 album, Twice Upon A Rhyme, was re-issued in 2010, and his new album, Welcome Up: Songs of Space and Time, was released in 2020.

Paul Levinson can be reached at levinson.paul@gmail.com.

Reblogged this on Paul Levinson.

LikeLike

ThanksPaul, you have been a great contributor, do you have an electronic version of the ETC special edition?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Rafe, Margaret here. I did some research. It is available in the JSTOR database. Hence, anyone affiliated with a University could download it. I could go to Cornell and get it there.

LikeLike

That would be great, Margaret!

LikeLike

Hi Rafe! No, I don’t have a digital copy of that special issue — I just a have one, original paper copy. But I’d be happy to see a digital version out there, and available to everyone for free.

LikeLike

Paul I think that Popper had a nuanced position on resisting the intolerant and that probably didn’t come through in the recent debate. It is essential to look at note 4 to Chapter 7 of OSIE and maybe what he wrote in the collection After Popper as well. He was very careful to specify how we might respond to intolerant speech and it is most likely that he only would have called for suppression where the speech was urging violence and there are already laws for that situation without any new ones to counter “hate speech.” You make the important point that legal protection is only required to protect speech that some people hate. Demanding the suppression of speech just because we don’t like it, or even hate it, is no argument at all.

The following passage calls for more discussion to clarify our minds and we are not obliged to agree with Popper of course. He wrote “I do not imply…that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. [this is where the going gets heavy!] But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational arguments.” [nowadays it seems most people just read their favorite literature and ignore the other side of the debate, which ends up in much the same place as if their leaders told them to ignore the arguments of the other side]. “We should therefore claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law.”

This has become more complicated than I realised when I started to comment:) Now we have to work out when we think a movement is preaching intolerance to a sufficiently serious degree to over-ride our default position on free speech – that is, no intervention unless actually urging violence.

There is more in the note on the paradox of democracy, or at least of majority rule, that is the possibility that the majority elect a dictator. He wrote “All these paradoxes can easily be avoided if we frame our political demands in the way suggested in section II (Chapter 7) …We demand a government that rules according to the equalitarianism and protectionism [nothing to do with trade protection]; that tolerates all who are prepared to reciprocate; that is controlled by, and accountable to, the public…some form of majority vote, together with institutions for keeping the public well informed, that is the best, though not infallible, means of controlling such a government (no infallible means exist.)

There are some important comments violence and free speech in Chapter 19 on The Social Revolution. He referred to persistent talk of violence, especially by radial and romantic elements of the socialist movement which makes the working of democracy impossible if the ambivalent rhetoric of revolution is adopted by a major political party. On the same lines the suggested that democracy can only work if the major parties are alert to the danger of power without checks and balances and also maintain standards of public debate and respect for free speech.

LikeLike

Thanks for the detailed, thoughtful comment, Rafe. This is indeed a complex and complicated issue. I’ve been thinking about it increasingly in the past year, because Trump is almost the epitome of why I don’t want the government to suppress any speech, and false information about COVID-19 and its treatment provides an example of the kind of information that I think should be suppressed. My position, at this point, is that yes, speech which urges violence and criminal activity is already and aptly against the law; no other kind of speech should be suppressed, unless it is spreading false medical information that could endanger lives (this is already restricted in the United States in rules against false medical advertising — I think it should restricted in all communication). Here’s an excerpt from a lecture I gave one of my online classes a few months ago that addresses this issue https://paullev.libsyn.com/us-senate-vs-twitter

LikeLike

Just doubling back to post a link this article, which shows the casual way in which people are using Popper’s paradox of tolerance these days https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/time-private-us-media-companies-stepped-silence-falsehoods-and-incitements-major-public-figure-1938-180976771/

LikeLike